Lost at sea -【Maritime supplu chain, Container ships, Pandemic】

2022.02.25 CHINADAILY.COM.CN

With the global supply chain severely disrupted by the pandemic, maritime trade flows have hit a bottleneck. Industry pundits say further digitalization may turn the tide, but digital fragmentation and cyberattacks present a challenge. Zhang Tianyuan reports from Hong Kong.

Chu Long-him - a deck cadet from Hong Kong aboard a container ship - found himself stuck at sea all of last year as the coronavirus pandemic upended his life. The 26-year-old couldn't disembark from the vessel and return home despite having holidays on three occasions.

Chu had started his trip in November 2020 under his contract with an international shipping company. During his first holiday when the ship anchored off the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, he tried to disembark and travel back to Hong Kong. But he was denied entry by the Dutch authorities for not having a visa to complete a 10-day quarantine. A similar fate befell him in Italy and Egypt in the following months.

Seafarers like Chu play an imperative role in the global economy as the bulk of cargo in standard-sized containers is transported by ships. The disruption to the turnover of sea crew and their repatriation at ports around the world has exacerbated the maritime supply chain's woes.

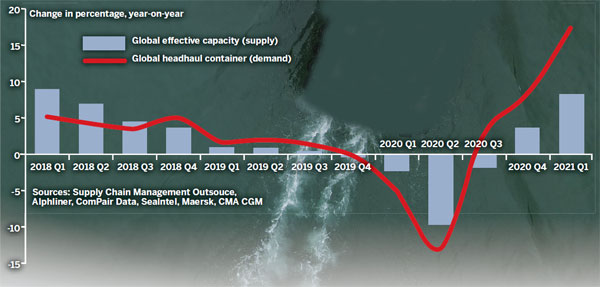

The shock to the supply chain started as global manufacturing capacity plummeted in early 2020 when factories worldwide, including those in China, were forced to shut down at the onset of the pandemic. It suffered another blow as self-confined shoppers took to e-commerce. The dire shortage of containers, coupled with worldwide port congestion, have kept supply-chain bottlenecks in the headlines over the past year.

COVID-19 has exposed the Achilles' heel of ports, shipping lines, container depots and even major logistics companies. Industry pundits say digitalization can help the logistics sector function smoothly despite the public health crisis. In their view, the worst was over as factories resumed production. But the maritime supply chain still faces enormous challenges in returning to the new normal amid shipping delays, digital fragmentation, cyberattacks and highly restricted movement of sea crew.

According to Nicolas de Loisy - president of Supply Chain Management Outsource and an industry expert at the Global Institute of Logistics - more than 100 ports worldwide have been constantly in lockdown since the pandemic struck. As a result, container ships have to wait for weeks to unload, with transit times and cargo deliveries taking up to 2 months. An estimated 10 percent of the 25 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) on 5,446 container ships and up to 70 million TEU containers have been immobilized. A Sea-Intelligence report showed that 68 percent of vessels have been delayed by an average of one week or more.

The delays have led to a huge demand for goods from China to Europe and the United States. The US and Europe import more than half of their consumer goods from China, whose stringent measures to contain the virus have enabled enough production to meet demand. Exports from China had been on the rise in 2021, having soared by 25 percent over the previous year. Trans-Pacific and Asia-Europe trade has thus drawn almost all the container ships available in the market, creating congestion at destination ports.

"We are at the peak of congestion. There is no indication so far this is getting any better," said Lars Jensen, founder and CEO of Danish company Vespucci Maritime, which provides analyses of the container shipping industry, "Delays will definitely be common this year as well. Normal operations globally are not gonna happen until the end of 2022."

Digital hurdles

Clogged ports in Europe and the US have stalled container ships coming to Hong Kong. According to the city's Maritime Department, the number of cargo vessels arriving in the special administrative region in the first 10 months of 2021 fell by almost 30 percent from the previous year. The seaborne freight discharge rate was down by 1.4 percent year-on-year in the third quarter of 2021, taking a toll on the imported food industry.

In Gurung, who owns Italian restaurant Sole Mio in Central, Hong Kong, said some food items like steak and cheese are running out of stock. Paolo Ponghellini, an executive committee member of the Hong Kong Imported Food and Beverage Association, said supplies have been unstable due to inconsistent food imports. "We don't know when the ships will arrive. We can't plan what to order or when."

Shipping delays have reduced the number of containers available in Asia. This has pushed the cost of sending containers between China and Europe and the US to record highs. Container spot rates for shipping from China to the US west coast soared by 422 percent between February 2020 and February this year. The number grew by around 700 percent in the same period when transporting to northern Europe, according to Lloyd's List Intelligence. Many containers were bumped off ships and forced to wait, adding to the long delays throughout the supply chain.

Hong Kong-based China Merchant Port Holdings - a leader in container port operations, as well as general and bulk cargo transportation - said availability and slow turnover of containers is one of the key bottlenecks in the logistics chain and will be hard to resolve in the very near future. Digitalization, automation and online platforms are crucial in reshaping supply-chain operations, it added.

Collaboration and data sharing should be achievable goals through the digitalization of the supply chain, but there are issues, according to Kris Kosmala, who holds multiple leadership roles in top global supply-chain and maritime technology companies.

"Connecting adjacent 'digital islands' is urgent in improving the sector's efficiency," he said. "We are still in the era of digital fragmentation."

Restrictions on the free flow of supply chain-related data and IT products across companies or borders due to any party's suspicions or security concerns, will rub salt into the maritime supply chain's wounds. Paper-based documentation still controls important parts of maritime trade, and key information about ships, products and health records of the crew must be viewed by each related authority and transaction party. As the pandemic has reduced most companies' manpower to a trickle, paper documentation has slowed down transactions in the industry.

Trading via paper documentation is too easily accepted as the "(natural) cost of doing businesses", Kosmala said, adding it's essential to establish a trade single window, as well as a maritime single window, and to have the two windows work together.

Documentation submitted through these two digital platforms can be viewed by all relevant agencies. Two systems linking up with scattered "digital islands" are important for ports to function efficiently, especially during the pandemic. They will help to reduce time in exchanging information and improve profits in port operations, according to Kosmala.

Cyberattack fears

Hong Kong implemented a trade single window voluntarily in 2018. Kosmala said it will be a major improvement on effectiveness if the platform becomes mandatory.

"When everybody is on the system, and all of the data in one place, the port authority can do data analytics and determine which port services need to be improved. The authority can figure out which commodity would take a longer or shorter time for processing," he said. However, Hong Kong lacks "a single, strong and innovative port authority that could bring all its terminal operators together and get them using a single maritime window".

At present, Hong Kong has nine terminals run by five different operators which had competed with each other until the Hong Kong Seaport Alliance was set up. The alliance connects only four operators and does not have any digital platform for information to flow across multiple terminals. In Kosmala's opinion, Hong Kong ports still have "digital islands" and the lack of a maritime single window is "detrimental" to arresting the decline in container throughput volumes.

Container throughput at Hong Kong ports slipped by 27 percent to 17.8 million TEUs from 2011 to 2021, according to the Hong Kong Maritime and Port Board's latest statistics.

"A port's strength is established at the authority's level. Deals, connections, volumes and ship calls can all be negotiated from the position of port power, something that's not possible at the level of an individual terminal," Kosmala said.

Overall, global turbulence has accelerated digitalization of the maritime supply-chain sector. Companies hard hit by the global supply-chain disruption have learned a harsh lesson that paper-based transactions and human-to-human contact businesses are no longer long-term options. More than 60 percent of respondents across industries have invested in digital supply-chain technologies since 2020 and plan to keep them, according to a survey conducted by McKinsey & Company.

"The supply-chain industry has historically been a low-tech sector," said Fraser Robinson, co-founder and CEO of United Kingdom-based Beacon - a supply-chain platform and digital freight forwarder. "However, in the past two years, data, connectivity and automation have become absolutely important in improving visibility, flexibility and decision-making within logistics. This is why we have seen such strong demand for Beacon's technology-driven solutions."

Jensen from Vespucci Maritime said he believes shipping lines and logistics companies will spend a lot of money in the next two years to upgrade their digital capabilities.

However, industry leaders are wary of possible cyberattacks on ports, shipping lines and key logistics service providers during the digitalization process due to a lack of investment in cyber defense capabilities in the sector.

Sabba Manyara - a Hong Kong cyber leader at global advisory company Willis Towers Watson - said the maritime industry in the Asia-Pacific region saw a 168-percent increase in cyberattacks between May 2020 and May last year. The sector appears to be the most targeted area in the world for ransomware and persistent State-sponsored threat groups.

Cyber extortion targeting the Danish owner of the world's largest container shipper Maersk in 2017 caused congestion at ports worldwide, including in the US, India, Spain and the Netherlands. Container deliveries were held up and it took weeks for the situation to return to normal.

The current disruption seen in the global supply chain is the worst in history and a cyberattack would make it worse, Jensen warned.